(Paris.) It was a more than slightly embarrassing moment when, having lived for years in France and deeming myself no longer a stammering novice to its language, I realized I was wrong.

The revelation hit me without a warning: “Niki de Saint Phalle” does not translate to “Nicky of the Holy Phallus”. It is not a pseudonym, chosen in irony by a feminist artist.

No, it is (or was) her actual name. To be precise, she was called Marie-Catherine Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle. Which is a superb example of how a noble name should be: long enough to signal (presumed) importance, yet a natural hindrance to sign too many cheques too hastily.

The de Saint Phalle family survived the French revolution with their heads still where they belong (to their opinion, not the revolutionaries’) and fared quite well afterwards with their own private banking house. Little Niki was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine (American readers: think Hamptons without the sea) and grew up in New York City, where she visited a catholic girl school. She modelled a bit, married the writer Harry Mathews, and in 1952 the couple decided to move to France. The reason given by her biographers is a disagreement with McCarthy era America, but De Gaulle’s France apparently was not what she’d expected either: The move resulted in a nervous breakdown. Potentially predisposed by centuries of inbreeding (hey, we’re talking about European nobility here!), she was diagnosed with the royal disease, schizophrenia.

Several electroshocks later, Niki emerged as a self taught artist. The rest is history and today, the Grand Palais honours Niki de Saint Phalle with a retrospective show.

The early works reveal a major talent with a strong will to equal the biggest names of her time: Tinguelyan assemblies (not satisfied with this, Niki was to marry Jean Tinguely himself in 1971) and Pollockish abstractions. Less important artists never leave this phase, but not so Niki de Saint-Phalle: In the early 1960s she found her own distinct style, and she knew what she wanted to express with her newly acquired voice.

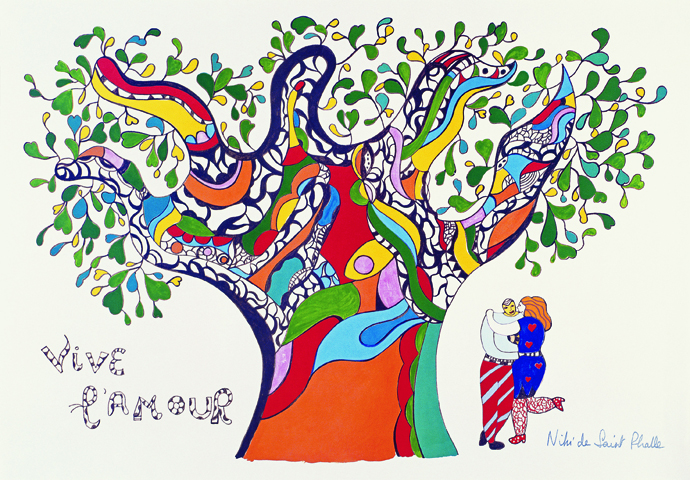

Braking overtly with her parents and class, Niki de Saint Phalle needed something else to identify with, and she found it in her sex (or gender, whatever). Historical aberrations from Marie-Antoinette to Victoria and Catherine wouldn’t hinder the identification of her family culture with “paternalism”. In an extract from a 1965 interview, Niki de Saint Phalle declares: "My art is female because I am a woman, I cannot do it different." From the same year date the first Nanas, larger than life female sculptures that would become her trademark works.

Originally the name of a Greek mythological character, “Nana” in French is used like “chick” is in English. It’s also the name of France’s most successful marque of female hygiene products, but we haven’t found any information as to the eventual payment of license fees from artist to marque or the other way round. Niki de Saint Phalle saw her Nanas as harbingers of a “new matriarchal world order”. She believed in duality, and denounced the male principle of “abstract brain” (others would say “Apollonian”) suppressing intuitive, humane, (“Dionysian”) feminity. Obviously, that’s why her Nanas resemble prehistoric fertility goddesses with many curves and tiny heads. In 1971, Niki defended motherhood as a full-time job, and demanded it to be paid for by the state (extract from another interview to watch in the Grand Palais exhibition). Sounds rather backwards, and discriminating, doesn’t it?

(Forgive me for being cynical, but it seems that back then feminism still meant more than equal rights to kill in wars and die from heart attacks. Nobody could yet foresee Angela Merkel and Pfc. Lynndie England as the ultimate manifestations of reached equality in a monosexual society. Unfortunately, the goal of changing society has long been replaced by the practise to subject not 49 but 100 per cent of population to the same dirty old values - left values following capitalist intentions, there goes your dialectics. Just my two etc.).

All the while, Niki refused to be a puppet on a string, and condemned marriage as an imposed life goal for women: Her Horse and the Bride is a sculpture made from dolls and other "girls’ toys". Grand Palais cites Simone de Beauvoir as an important influence to the artist, but doesn’t clarify on the apparent contradiction between Niki’s dualism and de Beauvoir’s beliefs (“Nobody is born a woman”) – would it be possible to accept education as the only reason for differences, yet ultimately insist on keeping them up? Because Niki de Saint Phalle thought both models equally important, not to be reduced to only one.

And there’re shots. Between 1961 an 1971 Niki de Saint Phalle organized shooting sessions. Carefully chosen objects were filled with colour bags of paint and covered with white plaster, then stood against the wall. The artist took a rifle and shot, female ejaculation the arty way. She also explained it as acts of counter violence (mind the old punk slogan: “destroy what destroys you”). Sometimes, harmless gallery visitors were invited to partake in the execution - sheerly unbelievable this was authorized without bullet proof walls and heavy protection clothes for the artist herself. Another era, indeed.

Not to forget, Niki de Saint Phalle challenged French politics and religion (with regards to the Algeria War) and realised outdoor projects expressively aimed at the “ordinary people” (most important: The Antonio Gaudi inspired Tarot Garden in Pescia Fiorentina, Italy). Once again, Grand Palais has organized a fascinating and exhaustive retrospective of a great artist.

Want to be taken for a connoisseur? Place yourself in front of Niki’s Black Widow Spider, rub your chin, nod and mumble knowingly: “Louise Bourgeois”. Or simply count the visitors doing so.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Grand Palais, 17 September 2014-02 February 2015

Comments